Access Denied

21 years after the Lucasville prison uprising, the media is still waiting for face-to-face interviews with the condemned prisoners.

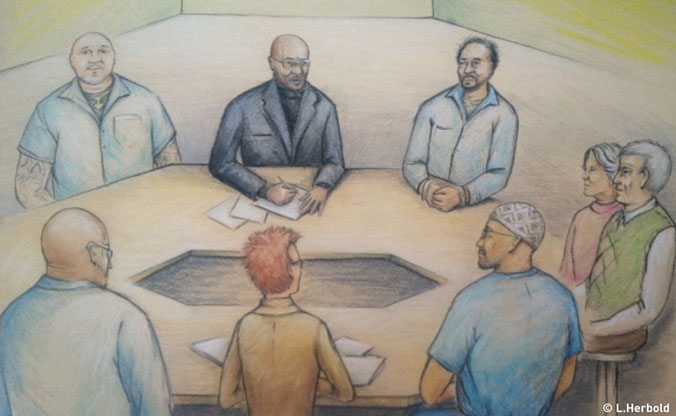

Artist Laurel Herbold’s imagined rendering of an actual legal meeting between prisoner Jason Robb, former ACLU of Ohio Legal Director James Hardiman, prisoner Greg Curry, ACLU Volunteer Attorneys Alice and Staughton Lynd, prisoner Siddique Hasan, ACLU of Ohio Managing Attorney Freda Levenson and prisoner Keith LaMar.

For more than two decades, Siddique Hasan, Jason Robb, George Skatzes, Keith LaMar and Greg Curry have claimed they are innocent of the crimes attributed to them during the 1993 prison uprising at Southern Ohio Correctional Facility (SOCF).Among other things, these five men accuse the state of coercing false testimony from other SOCF prisoners in order to convict them. They have spent years in solitary confinement, soliciting media attention in an attempt to convince the publicand ultimately the court systemthat they do not belong where they are.(clockwise from top left) Jason Robb, Siddique Hasan, Greg Curry and Keith LaMar are all incarcerated at Ohio State Penitentiary in Youngstown, Ohio. Not pictured is George Skatzes, who is incarnated at the Chillicothe Correctional Institution (photo courtesy of Siddique Hasan and Greg Curry).

In response, the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (ODRC) has completely banned face-to-face media contact with these men, arguing that they are too much of a security risk to be allowed to tell their stories in person.

In late 2013, the ACLU of Ohio filed a lawsuit challenging this ban. The suit was filed on behalf of Hasan, Robb, Skatzes, LaMar and Curry, as well as one teacher and four reporters, including Pulitzer Prize winner Chris Hedges.

Read the ACLU of Ohio’s complaint challenging the ODRC media ban on the Lucasville prisoners.

We filed this suit because the ODRC is violating the First Amendment rights of the prisoners and of the press. It’s not hard to see that their actions have very little to do with security and everything to do with silencing an uncomfortable conversation about the Lucasville uprising.

For proof, consider that many other death row inmates in Ohio have been granted face-to-face access to the media. They include spree killer John Fautenberry, neo-Nazi murderer Frank Spisak, and convicted arsonist Kenneth Richey, who has since been released from death row.

In all, Ohio prison officials have approved nearly two dozen media interviews with other death row inmates while denying each and every request for face-to-face interviews with the five Lucasville prisoners. This ban is a special form of extended vengeance, reserved only for them.

These prisoners are complicated characters, and the Lucasville uprising is a complex story.

Hiding these complexities behind a wall of censorship will not make them go away.

The Basics

21 years ago, on Easter Sunday 1993, more than 400 inmates at an overcrowded prison in Lucasville, Ohio staged an 11-day prison uprising. In the ensuing violence, nine inmates and one corrections officer lost their lives.

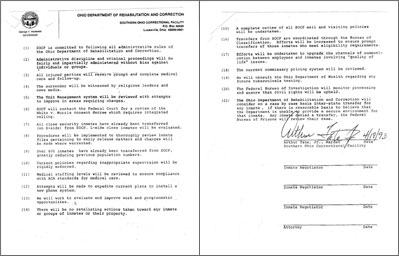

Read the 21-point Agreement that ended the standoff at SOCF.

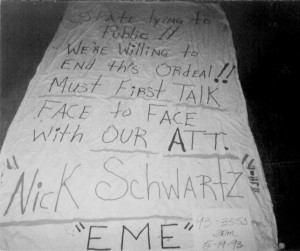

In an attempt to end the standoff, ACLU volunteer attorney and longtime advisor Niki Schwartz was asked by state officials to meet with three prisoner negotiators. With his help, the two sides eventually came to a 21-point agreement that brought an end to the uprising.

In the aftermath, three of the chief prisoner spokesmen, Siddique Hasan, Jason Robb and George Skatzes, were sentenced to death (along with prisoner Namir Mateen) for their alleged role in the murder of a corrections officer.

Prisoner Keith LaMar was also sentenced to death for his alleged role in organizing the murders of other prisoners during the first hours of the uprising. Prisoner Greg Curry received a life sentence on similar charges.

For some this is where the story ends. For those looking to dig deeper, it’s only the beginning.

The “Luke”

21 years ago, SOCF was a different prison from the one it is today. The facility was shockingly overcrowded, and allegations of violence, brutality and corruption plagued both sides of the bars.

Longtime activist and ACLU volunteer attorney Staughton Lynd chronicles many of these problems in his book, Lucasville: The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising. Lynd’s researchwhich provides much of the historical context for this articleshows that those in the know predicted big trouble in the “Luke” years before the actual uprising took place.

Big trouble eventually came in the form of a mandatory tuberculosis test which required an alcoholic substance to be injected into the body. This practice violated the religious beliefs of a number of Sunni Muslim inmates.

Siddique Hasan was an influential voice among these inmates. He was also less than a year from a meeting with the parole board and had been living in the prison’s honor block. Hasan says the Muslim inmates at SOCF planned an organized protest to pressure officials into giving them an alternative TB test. When other angry and frustrated inmates joined in, the protest quickly morphed into something much larger.

According to Niki Schwartz, the TB test was just the spark. The tinder was a serious overcrowding problem, combined with forced integration rules that put inmates of different races into the same cell.

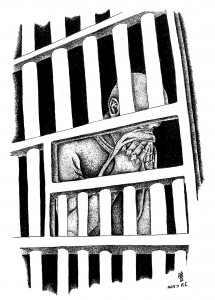

Prisoner Jason Robb’s rendering of a prisoner in his cell (image courtesy of Staughton Lynd).

“We’re talking about cells the size of small bathrooms,” says Schwartz. “Loving spouses would be at each other’s throats if they were forced to live together in a space this small, and these prisoners were not loving spouses. Nearly all of the consequences in the aftermath [of the uprising] were negative, but one of the few positives was that SOCF finally became a single-cell prison.”

As violence quickly erupted inside SOCF, inmates overtook a guard with keys and seized control of more and more territory. They armed themselves with weight-lifting equipment and eventually the batons of the guards they captured.

By the end of the day, inmates were in control of an entire cell block. Seven prisoners were dead (two more would later be killed). Four badly injured guards had been released, and eight others were being held hostage. One of them was Robert Vallandingham.

“Bobby”

Most of the people involved in this story seem to be able to agree upon one thing: Robert Vallandingham was respected and well-liked at SOCF. He was murdered on April 15, amid stalled talks between prisoners struggling to keep control of the uprising and state officials struggling with their chosen negotiation strategy.

By all accounts, it turned a bad situation into a total nightmare.

“Vallandingham was regarded as a humane and well-liked guard,” says Schwartz. “That only made his murder that much more incomprehensible.”

At the time of the uprising, the three main prisoner groups at SOCF were the Sunni Muslims, the Aryan Brotherhood and the Black Gangster Disciples (BGD). After the initial chaos subsided, these three groups segregated themselves in different parts of the occupied cell block. They were working together when necessary, but there was tension and differences of opinion about what to do next.

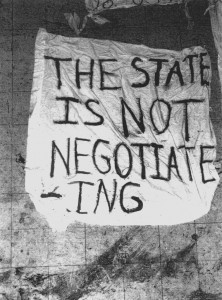

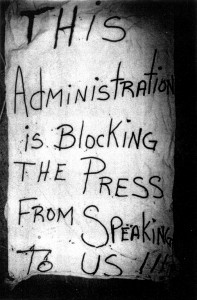

As the uprising dragged on, prisoners began to grow angry with the pace of negotiations and attempted to deliver their own messages to the crowed gathered outside (photo courtesy of Staughton Lynd).

At the time of Vallandingham’s murder, Hasan (a Sunni Muslim), Skatzes and Robb (members of the Aryan Brotherhood) and another prisoner named Anthony Lavelle (a member of the BGD) claim they were attempting to keep the groups together to negotiate an end to the standoff.

Two guards held hostage during this tense time later testified that Skatzes took active steps to protect their safety. Other witnesses testified that Hasan used his influence among Muslim inmates to have suspected informants and hostages moved to more secure areas, where they could be better protected.

Robb eventually replaced Skatzes as a prisoner negotiator. According to Niki Schwartz, he also used his position as negotiator to push for a peaceful and orderly end to the standoff.

For his part, Anthony Lavelle later testified against his fellow negotiators, claiming the group made a collective decision to kill Robert Vallandingham in order to show law enforcement officials that they were serious about their demands.

Read Jason Robb's full letter to the ACLU of Ohio, discussing the Lucasville uprising.

Hasan, Skatzes and Robb all deny this claim. Other prisoners later alleged that Lavelle represented a more hard-line group of inmates, a group that decided for themselves a guard needed to be killed and acted accordingly.

It is known for certain that on the morning of Vallandingham’s murder, George Skatzes was on the phone with negotiators, warning them that hostages were in grave danger if water and electricity were not restored to the prison. Sometime later, he reportedly learned that a hostage had been killed, according to prisoner testimony.

“[A] member of the Aryan Brotherhood. . . recalled under oath that he sat next to George Skatzes when Skatzes was on the phone with negotiators on the morning of April 15,” writes Staughton Lynd on page 61 of Lucasville: The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising. “Lavelle came in and handed George a note. . . George read the paper out loud. It read, ‘The hard-liners are taking over’.”

Later that day, Skatzes personally released a hostage. Afterward, he made a prison radio broadcast, giving “condolences to Bobby’s family” and making it clear that there was major dissension among the prisoners about what had happened that day. Following the broadcast, he was removed as prisoner spokesman by inmates who felt he had been too conciliatory. Jason Robb took his place.

Today, Siddique Hasan calls Vallandingham’s killing “senseless” but claims there was very little he could do to control the angriest prisoners.

Read Siddique Hasan's full letter to the ACLU of Ohio, discussing the Lucasville uprising.

“As the prayer leader and spiritual head of the Sunni Muslims, I certainly had some level of influence over those people who practiced that faith,” says Hasan. “But we were a distinct minority of the inmates in Lucasville and in the uprising area in particular. The vast majority of the inmates who stayed in the uprising (over 400) were completely beyond my ability to control.”

There are many accounts of what exactly transpired that fateful day; we may never know the full truth of how Robert Vallandingham died. What is certain is that his murder was tragic for everyone, whether they knew it or not.

“None of us can know for sure of course, but I believe things would have been very different if he had not been killed,” says Schwartz. “His death created enormous pressure and a great deal of inflexibility in the later prosecutions. After that, they saw no other option but to give someone the death penalty.”

The Negotiators

Niki Schwartz was called to SOCF after Vallandingham’s murder to serve as legal counsel for the negotiating prisoners. When he arrived, he sensed a palpable division between those who wanted peace and those who wanted an opportunity to avenge the guard’s senseless death.

“At that point it was really another Attica waiting to happen,” says Schwartz. “I sensed a lot of tension between the hawks and doves on the law enforcement side. There were some who wanted to storm the prisoners, but there were others who still wanted a peaceful solution.”

Prisoners eventually demanded and received a lawyer, whose name they believed to be “Nick Schwartz” (photo courtesy of Staughton Lynd).

The three main prisoner groups had collaborated on a list of 21 demands, and state officials asked Schwartz to deliver their response to the negotiators. Outside, on opposite sides of a prison fence, Schwartz prepared to meet with Hasan, Robb and Lavelle face to face.

“The first thing I asked [state officials] was if they actually intended to abide by this agreement,” says Schwartz. “I knew they would be free to ignore it later since it had been obtained as the result of a hostage situation, but they told me there were many things in the agreement that they should have already been doing. They pledged to abide by the terms.”

When he met with the prisoners, he found that their verbal demands dealt almost exclusively with the conditions of their surrender.

“They were very fearful of being stormed by the guards, who obviously had a great deal of hostility toward them at that point,” says Schwartz. “The first thing they asked was whether or not the agreement was legally binding. I told them the truth; it was being extracted by the holding of hostages so the state could legally repudiate it if they wanted. I also told them I would scream to the high heavens if the state went back on their word.”

At the end of that day, Schwartz presented the results of the negotiations to law enforcement officials, who were cautiously receptive. He then held a press conference at the request of the prisoners, who asked him to point out that they were negotiating in good faith and that they wanted a peaceful solution.

Coffee Break

The next time Schwartz sat down with the prisoner negotiators it was inside the prison to hammer out the details of a final surrender. The prisoners had been without water, electricity or toilets for over nine days and had very little food. They were exhausted, and tensions were high.

“They came in looking very rough,” says Schwartz. “The first thing they asked for was a cup of coffee. Given the climate, I wasn’t sure they were going to get anything from anybody.”

But a funny thing happened. The Ohio State Highway Patrol officer in charge of the scene not only retrieved coffee for the negotiators -- he served it to them himself. With tensions lowering, he proceeded to walk the group through the prison gym where the proposed surrender would take place, answering their questions about how everything would be done.

“I thought it was a brilliant move,” says Schwartz. “He built a great deal of rapport in that moment by treating them like men, and it paid off. His role wasn’t given nearly as much publicity as my role, but I try to talk about it whenever I can.”

See the Columbus Dispatch’s gallery of archived images from the uprising.

The prisoner negotiators remained concerned about some prisoners using the surrender as a final opportunity to settle grudges, so they demanded that they be allowed to bring the inmates out in small groups. Finding a news outlet willing to televise the surrender was also critical in convincing the prisoners that they would not be stormed by furious guards immediately after giving up their hostages.

In the end it took seven hours to complete the surrender, with all of the negotiators working together in an attempt to avoid problems.

“They impressed me, and none of my contact with them since has changed my mind,” says Schwartz of the prisoner negotiators. “I don’t know for sure what ultimate role each of them played in all of the events, but my impression of them was that they were extraordinarily bright. If life had dealt them different cards, they might well have been leaders in law-abiding society.”

The Aftermath

To understand what happened next, you must first understand the immense pressure that was placed on the State of Ohio to make people pay for what had just happened at SOCF.

Not only had the uprising claimed the life of a guard; it had exposed serious and embarrassing problems with the prison system. The state wanted quick and decisive convictions.

Unfortunately, investigators were dealing with one of the largest crime scenes ever encountered in Ohio. It proved very difficult to gather any physical evidence, or to make any concrete determinations about who did what during the 11-day standoff.

The investigation totally overwhelmed the small Scioto county prosecutor’s office, so a special prosecutor was appointed to manage the process. No such accommodations were made for similarly overwhelmed public defenders. Schwartz likened the allocation of legal resources to “nuclear weapons versus slingshots.”

Southern Ohio Correctional Facility as it appears in 2014 (google maps photo).

In this climate, the prosecution immediately set about turning SOCF prisoners into cooperating witnesses. There were dozens of varying accounts of the uprising, but in the end, those who chose to testify against other prisonerseven those who admitted to very serious crimeswere taken at their word and given plea deals.

Those who did not testify against their fellow prisoners were labeled as the ringleaders of the uprising and prosecuted as aggressively as possible.

Who was actually telling the truth remains difficult to determine.

“I’m not accusing anyone of not caring about what actually happened, but I do believe that there was a special effort made to pin the violence on the perceived leaders to make examples of them,” says Schwartz. “I truly believe they were targeted because of their high profile. There is a lot of evidence to suggest that other prisoners were promised special consideration if they had evidence against the negotiators.”

“Ultimately, I think this was a very short-sighted thing to do,” adds Schwartz. “Sooner or later there will be another problem at a prison. The state is trying to execute the people who negotiated an end to the last one; so what inmate in his right mind is going to play the role of peacemaker next time?”

“I’m havin’ one hell of a time puttin’ all this together”

The prisoners convicted in the aftermath of the uprising allege a wide range of coercion, corruption and deceit on the part of prosecutors and cooperating witnesses who testified against them.

Hasan often points out that one of the state’s primary witnesses against him was actually indicted for the hands-on murder of Robert Vallandingham. When a hung jury failed to convict him, the state agreed not to try him again in exchange for his testimony against other high profile prisoners.

Read Keith LaMar’s full letter to the ACLU of Ohio, discussing the Lucasville uprising.

“I’m havin’ one hell of a time puttin’ all this together,” writes Skatzes in a 1995 letter to one of his accusers. “I have run this through my head so many times; it is to the point of driving me crazy! I will never figure out how, what did they do to you to get you to lie like you are?”

Greg Curry and Keith LaMar were never accused of masterminding the uprising, or of conspiring to kill Robert Vallandingham. Both eventually found their way outside when the trouble began and stayed in the prison yard until they were rounded up by authorities on the first night of the uprising.

Read Greg Curry’s full letter to the ACLU of Ohio, discussing the Lucasville uprising.

Both were later accused of participating in “death squads” that killed other prisoners suspected of being informants. They were convicted based on the testimony of other prisoners, some of whom cut deals to avoid punishment for crimes they admitted to committing.

This short compilation barely scratches the surface of the prisoner’s long list of claims against those who convicted them. These claims are addressed more fully in Lynd’s book, Lucasville: The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising, which was also turned into a stage drama in 2007.

Belief is Complicated

People often need clear-cut heroes and villains. In this story they are very hard to find.

As long as there are questions in the minds of the public about the cause of the uprising and the convictions of those involved, there will be no true resolution to this story.

(photo courtesy of Staughton Lynd)

Siddique Hasan, Jason Robb, George Skatzes, Keith LaMar and Greg Curry want you to believe their claims. But belief is complicated. You can read their words or hear their voices; but sometimes it takes looking into someone’s eyes to determine whether you believe they are telling the truth.

This is the look the media is searching for when they seek access to these five men.

This is the look the state of Ohio has banned.

“They rationalize it by saying these inmates are different, but it doesn’t pass the smell test,” says Schwartz. “It’s obviously retaliatory, and in my opinion that makes it a violation of the 21-point agreement they signed.”

“I’m not asking you or the public to take my word for anything,” says Keith LaMar. “View the evidence and decide for yourselves whether you think I deserve to live or die.”

Documents

- LucasvilleMeetingSketchLaurelHerbold.jpg

- HanrahanEtAlV.MohrEtAl-Complaint2013_1209.pdf

- Lucasville21PointAgreement1993_0418.pdf

- LucasvilleJasonRobbIllustration.jpg

- LucasvilleStateIsNotNegotiating.jpg

- LucasvilleJasonRobbStatement2014_0410.pdf

- LucasvilleSiddiqueAbdullahHasanStatement2014_0404.pdf

- LucasvilleNickSchwartz.jpg

- LucasvilleSOCFCurrent.jpg

- LucasvilleKeithLaMarStatement2014_0324.pdf

- LucasvilleGregoryCurryStatement2014_0321.pdf

- LucasvilleAdministrationIsBlockingThePress.jpg