It was a chilly October last year when my colleague and I visited the super-maximum security (super-max) Ohio State Penitentiary in Youngstown. Before entering, I thought there was nothing more restrictive than the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility, aka Lucasville prison. I could not have been more wrong.

Simply put, the building was built exclusively for solitary confinement. People in Ohio prisons are separated by security classification, and only levels four and five are housed here. They spend 23 hours a day behind a steel door in a cell the size of a parking space. If allowed out of the cell, a person is fully shackled from hands to feet.

The Reality of Solitary

The one-hour recreation period is meant for solitary activity. During this coveted time outside the cell, a person can play basketball or do pull ups and dips inside a cage the size of a walk-in closet.

In Ohio, 42 people with mental illness are housed in this facility. They told us that typically people are in the maximum-security solitary conditions for an average of four to five years.

The U.S. Supreme Court and almost all international human rights groups and medical professionals say solitary confinement is akin to physical and mental torture, yet Ohio continues the practice.

Prisoners in the most restrictive setting in this prison who are there for one or more years are put on elevated monitoring because of the mental deterioration that happens while in solitary.

What We Noticed

Programming is offered inside the cell on a television or inside a cage. Pre-recorded, out-of-date videos play that, when described, reminded me of 70s-style videos I used to make fun of in elementary school.

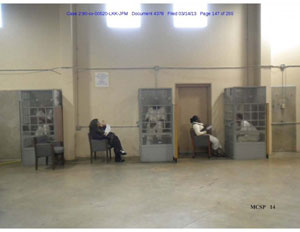

The in-person programming is done in crescent-shaped cages. The staff kept correcting us by calling them programming booths. Semantics mean little when your life is essentially lived in a cage. Yet, 50 people are released from these settings each year directly into the community, with little rehabilitation.

Even health-care and individual programming happen in a private cage. Meaningful programs are few and far between. Ohio prisons gets millions of taxpayer dollars each year, yet are not required to provide quality, rehabilitative programming to inmates, nor are they required to show effectiveness to taxpayers.

During our tour, a corrections officer used pepper spray on an inmate. Even after 20 minutes to allow the spray to dissipate and still separated by doors and walls, the effect from the pepper spray was unbearable. A prisoner, who was not coughing or experiencing any symptoms, told us the smell is hard to get used to. I wondered what the prisoner did to deserve pepper spray, as people are allowed out only one hour a day and are fully shackled.

What I Will Always Remember From Touring Lucasville & Ohio State Penitentiary

The air is stifling; I felt the need to leave immediately upon entering the prison. The mental health unit at Lucasville is smaller, more confined, and has less sunshine. It also is eerily quiet.

When I asked the warden at Lucasville what people do in their recreation cages, he said they often forego exercise, instead taking advantage of the only opportunity they have to engage in conversation with other prisoners, even if that’s done through a wire barrier. While at the Ohio State Penitentiary, recreation is essentially an extension of the solitary confinement prisoners experience while in their cells.

The U.S. Supreme Court and almost all international human rights groups and medical professionals say solitary confinement is akin to physical and mental torture, yet Ohio continues the practice.

This prison was the most oppressive place I have visited. When I left, I had a renewed sense of purpose to ensure that the conditions are humane and rehabilitative.