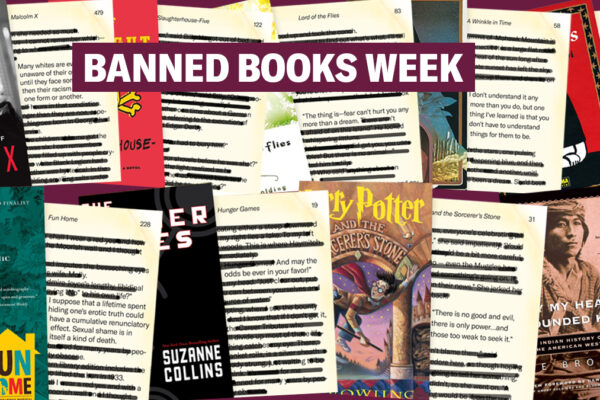

While many of us have our eyes on Buckeye football, fall foliage, and Halloween decorations during the first week of October, it also happens to be Banned Books Week.

At the ACLU of Ohio, we are committed to fighting government censorship. From books and radio to film, television, and the internet, we work to ensure Ohioans have the right to learn without the fear of government suppression. Book banning is one of the most common and pervasive forms of censorship in our society.

Unfortunately, this year’s Banned Books Week comes at a time when book challenges and bans are more common than ever. The American Library Association (ALA) tracked 1,269 challenges to 2,571 individual books in 2022, a record since the organization began tracking this data over 20 years ago. This figure is nearly twice the 729 challenges reported in 2021. These figures only encompass challenges that were reported—the actual number is likely higher.

What is the difference between a book challenge and a book ban?

How is a book challenge different from a book ban? I am glad you asked! Before a book can be banned (and thus removed from the shelves of a public library or school library), someone must come forward and file a challenge to that book.

Once a book is challenged, the governing entity of that institution—usually a school district’s superintendent and board of education or a public library’s board of trustees—must decide whether to remove the book based on their internal policies. These policies vary by institution. An institution may also decide to restrict access to a book on an age basis or some other basis, rather than removing it entirely.

In 2022, challenges were just about evenly split between schools (51 percent) and public libraries (48 percent), with the remaining 1 percent occurring in college libraries or elsewhere.

Here in Ohio, we saw the ninth-most challenges reported of any state, with 34 challenges of 79 titles.

The distinction between challenges filed and the individual titles that are challenged is also an important one. According to the ALA, the vast majority of challenges before 2020 applied to just one book and often came from an individual. However, in 2022, 90% of challenges sought to ban multiple books. Groups like the ALA see this explosion in mass challenges as an indication of how well-organized the groups who advocate for censorship have become.

It is also vital to talk about the stories these groups are trying to censor—primarily, books about race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity; many of the most commonly banned books contain all of the above. This is no coincidence. Those pushing for these bans are singling out queer, Black, and brown authors because of who they are and what they have to say.

The 12 most frequently challenged books in 2022, per the ALA, are proof-positive of this, featuring titles like Maia Kokabe’s Gender Queer: A Memoir and Lorain native Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. Over the years, very few authors’ works have been targeted more frequently than the renowned, Pulitzer Prize-winning Morrison’s.

Even when books are not challenged or removed from the shelves, those who would seek to censor them find other ways to do so.

Case in point: In July 2022, author Jason Tharp was prevented from reading his book It’s Okay to Be a Unicorn at Buckeye Valley West Elementary after parents and school board members complained that the book conveyed a pro-LGBTQ+ message. The school’s principal then instructed Mr. Tharp not to read the book during his visit.

The ACLU of Ohio responded with a letter expressing First Amendment concerns. The Buckeye Valley School District’s new superintendent sent an encouraging reply, committing to respect students’ and speakers’ free speech rights in the future.

The bottom line is that students have a First Amendment right to have access to materials in their schools’ libraries free of viewpoint discrimination, and an outside speaker like Mr. Tharp has a right to be free of viewpoint discrimination while visiting a school.

How can I fight against censorship?

You might ask “what can I do to advocate against censorship if I am not a decision-maker in these processes or a lawyer?” The short answer is that you can organize and make your voice heard!

Communities across Ohio have made it clear that they do not want their school libraries and public libraries to be places where books are censored and voices are silenced, particularly queer, Black, and brown voices.

In fact, many attempts at book banning and other forms of censorship are activating wide swathes of these communities—whether it’s students at Big Walnut High School in central Ohio, parents in the Cleveland-area Mentor School District, community members at the Muskingum County Library in southeast Ohio, or students and parents at the Cincinnati-area Forest Hills Local School District.

Small steps like showing up to your school board’s next meeting or writing to your elected officials in support of the right to learn can make a big difference. Even the simple act of reading a banned book (and encouraging your friends to do so) is powerful.

Statewide organizations like Honesty for Ohio Education have stepped up to the plate, too. They advocate not just for the freedom to read, but also the freedom to receive an honest education grounded in truth, facts, and diverse perspectives.

Additionally, the ACLU of Ohio Action Team advocates every day for change at the local and state level. Fighting censorship is very much a part of that work. And if you’d like to learn more about the fight against banned books across the country, the national ACLU has you covered.

In short, there are so many ways to get involved. We can and we must fight back against these attacks on our First Amendment rights. Join us in celebrating this Banned Books Week at your local public library, school library, or community.